by C. T. Heaney

by C. T. HeaneyAnyone who spent sufficient time listening to rock radio in the late 1990s should have been struck by how profoundly weird much of the music making the charts was. There was something about the confluence of time, the prevailing aesthetics, and an economy flush with prosperity that resulted in a musical landscape dotted with all manner of oddities which somehow, over and over, kept breaking through to a wider audience.

I started paying attention to music in 1996, and perhaps my vision is dulled by a lack of insight into the previous few years. To be sure, there was a fair bit of weird music hitting the charts all through the nineties (hello, Flaming Lips' “She Don't Use Jelly”), and the fact that bands like, say, Tad, King Missile, or Primus even had major-label contracts in the first half of the decade is evidence of something unusual being in the water.

There's an already-well-established historical narrative for why this should be so, and I think that explanation is valid, so I will summarize it.

In the wake of the sudden and explosive success of Nirvana in

1991, “grunge” swiftly became the biggest musical buzzword in more than a decade, and in the band's wake, major labels and larger independents started snapping up virtually every band in the Pacific Northwest they could slap a label on. As this new sound gained momentum – though it imploded very quickly – it amounted to a wholesale paradigm shift in what a popular rock band should look like; it reestablished the mainstream validity of punk-derived notions: authenticity, resistance to authority, anti-corporatism, pervasive irony, and ugliness/rawness/abrasiveness as aesthetic ideals. It turned them into philosophies that every streetcorner kid adopted and demanded from their musical role models.

1991, “grunge” swiftly became the biggest musical buzzword in more than a decade, and in the band's wake, major labels and larger independents started snapping up virtually every band in the Pacific Northwest they could slap a label on. As this new sound gained momentum – though it imploded very quickly – it amounted to a wholesale paradigm shift in what a popular rock band should look like; it reestablished the mainstream validity of punk-derived notions: authenticity, resistance to authority, anti-corporatism, pervasive irony, and ugliness/rawness/abrasiveness as aesthetic ideals. It turned them into philosophies that every streetcorner kid adopted and demanded from their musical role models.Thus, weird bands who reflected some or all of these ideals suddenly became potential buzz-bin successes, and labels like Atlantic, Geffen, Giant, and many others started throwing a lot of money at bands that, five years earlier, would never have made it out of county except in their own vans. By the middle of the decade, a new crop of bands had been found and signed that hewed rather closely to the Seattle sound, but which increasingly came from farther and farther away (Candlebox; Seven Mary Three; Collective Soul; Bush; Silverchair). These bands were successful, but so were more mainstream acts that looked back to '70s roots music and '80s college rock for inspiration (Hootie & the Blowfish; Gin Blossoms; Toad the Wet Sprocket; Dog's Eye View; Matchbox 20). This latter movement – a critical Port-a-Potty, and still without its own snappy subgenre designation – was a major force at the time, and still remains profoundly influential and popular, in addition to having produced some of the decade's most endurably compelling ditties.

These two strands – which occurred at the same time, and which intermingled, but which I see as musically distinct – made up the bulk of what was hitting rock radio at the time. They were the “normal”, to which may be added a few hugely successful but somewhat freestanding other groups such as the Red Hot Chili Peppers, the Beastie Boys, and Green Day. These fit rather illy under the umbrella of “alternative”, but they were generally grouped into it at the time (our mania for categorization was no less obsessive then than it is now.)

“Grunge” gave way to “alternative” as a descriptor for new music as it broadened into something that reflected less a particular sound and more an orientation towards making music alternate to mainstream pop, to the dance groups, slick R&B singers, and cocky rappers who then (as now) were generally the most popular and best-selling musical artists of the time.

I think the expansion of the idea of alternative rock was confusing to A&R reps, and I think it was confusing to many musicians, too. There was so much to work with – rock, pop, folk, hip-hop, techno and other electronic musics. Musicians were making strange music, as they always did, and label scouts were looking for hits, as they always did; both continued playing their roles perfectly through the 1990s. But because the new aesthetics were so confusing, many, many musicians started with bizarre substrates and managed to graft a pop hook, or a tricky rhythm, or something catchy, onto it, and thereby convince a label that one or two 3-minute surefire singles were worth six-figure advances.

And this happened dozens of times over. And – and this is important – radio stations still broke bands; they still had enough independence to start playing whatever wacky shit ended up in their USPS totes in order to give it a chance to catch on. Nobody really knew where music was going. Nobody knew what they were doing – not the artists, not the suits, not the deejays at the stations. Anything could catch on – anything.

The poster child for this carnival show is Beck. Beck should not be famous, and we are all richer as human beings because he is. However, he was a space-cadet oddball when he first landed airplay in 1994 with “Loser”, a song that is still shockingly bizarre after all these years. What the hell do you call that song? It's rapped, but it's not a rap song; it uses samples and is heavily beat-driven, but that still doesn't bring it around to hip-hop; features a slide guitar and is by a musician with folk experience, but can't seriously be called folk or folk-rock or blues; it's ridiculously infectious, but is pop only in the broadest, most inclusive sense of that word. We called, and call, it “alternative” because it makes no sense to call it anything else.

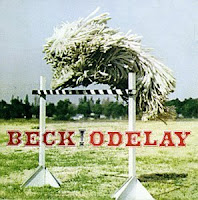

Beck's early discography could be listed in the dictionary under “hit-or-miss”--it's as quirky as they come. His landmark 1996 release, Odelay, carpet-bombed rock radio and MTV with a raft of super-catchy, super-weird singles, and alongside it--or directly after it--came all kinds of sounds that deformed, demented, and outright detonated what pop and rock were supposed to be.

And if you had the radio on at just the right time, you heard this nutty stuff coming forth, and chances are you took some of it home with you, too. Like “Standing Outside a Broken Phone Booth with Money in My Hand” by Primitive Radio Gods. Have you ever listened to their album Rocket? No, of course not, even if you did buy it – and hundreds of thousands of people bought that record. It's a lo-fi four-track home demo made by a barely competent songwriter, and it's rather charming in its amateurishness and possibly unintended humor, much like those first few Beck records. But the one thing that really works – that worked spectacularly, shooting up the charts in the summer of 1996 – is that deathless single, built around a ghostly piano-and-synthesizer background, a hip-hop drum loop, and a sample of B.B. King – B.B. King!

Try some other examples. “Your Woman” by White Town. “Circles” by Soul Coughing. “Head” by Tin Star. “Possum Kingdom” by the Toadies. “Better Days” by Citizen King. “In the Meantime” and “Mungo City” by Spacehog. “Pardon Me” by Incubus (yeah, remember how fucked it sounded when you first heard it?). “Stepping Stone” by G. Love and Special Sauce. “Banditos” by The Refreshments. “Place Your Hands” by Reef. “The Oaf” by Big Wreck. “Wait” by Huffamoose. “Flagpole Sitta” by Harvey Danger.

“Sex and Candy” by Marcy Playground. “Pepper” by the Butthole Surfers. “Hooch” by Everything. “Lump” and “Peaches” by The Presidents of the United States of America. “The Sweater Song” and “Buddy Holly” by Weezer. Even pop got weird – really, “Tubthumping” and “Amnesia” by Chumbawamba? “Virtual Insanity” by Jamiroquai? “Steal My Sunshine” by Len? This is strange, strange stuff. Some of it broke harder than others, but it was all part of the rich tapestry. Even the flash-in-the-pan movements, which we now recognize as movements, sounded totally odd and new at the time they started showing up. Like neo-swing (“Hell” by Squirrel Nut Zippers? “Zoot Suit Riot” by Cherry Poppin' Daddies?), or third-wave ska (“The Impression that I Get” by Mighty Mighty Bosstones? “Sellout” by Reel Big Fish?), or neo-'60s (“Walking on the Sun” by Smash Mouth?).

“Sex and Candy” by Marcy Playground. “Pepper” by the Butthole Surfers. “Hooch” by Everything. “Lump” and “Peaches” by The Presidents of the United States of America. “The Sweater Song” and “Buddy Holly” by Weezer. Even pop got weird – really, “Tubthumping” and “Amnesia” by Chumbawamba? “Virtual Insanity” by Jamiroquai? “Steal My Sunshine” by Len? This is strange, strange stuff. Some of it broke harder than others, but it was all part of the rich tapestry. Even the flash-in-the-pan movements, which we now recognize as movements, sounded totally odd and new at the time they started showing up. Like neo-swing (“Hell” by Squirrel Nut Zippers? “Zoot Suit Riot” by Cherry Poppin' Daddies?), or third-wave ska (“The Impression that I Get” by Mighty Mighty Bosstones? “Sellout” by Reel Big Fish?), or neo-'60s (“Walking on the Sun” by Smash Mouth?).And let's not forget – the first time that a lot of people heard Eminem's “My Name Is” was on rock stations, who played it as a novelty hit rather than hip-hop. It was a hectic time, where there was almost no center, and certainly no sure direction. The only common thread I can find between these songs, besides rough temporal proximity, is perhaps a vague sense of wry wit in the performances and lyrics of the songs. People looked forward, they looked backward, they looked around to other cultures, other places. It was a rich time, far richer than it's given credit for, precisely because it had no clear idea of what ought to come next out of this idea of “alternative”.

And so, eventually, “alternative” came to mean...pretty much everything.

Around the end of the decade, courses began to set themselves, and rock regularized. Rap-rock enjoyed its second moment in the sun, as it inevitably would and possibly will again. A new strain of forceful and anguished rock, directly inspired by grunge but increasing the production values and taking more of its heaviness from thrash, set the tone for the new mainstream rock of the 2000s. Soon after, Dashboard Confessional, Saves the Day, and Jimmy Eat World broke emo, which was punk's newest progeny and, in a very real sense, became the new “alternative” for a new decade. Meanwhile, critics demanded that rock return to other ages (though it had been doing that all along) and bands reinventing other strands of the 1970s and '80s (The Strokes, The White Stripes, Interpol) were heralded as saviors of a musical style that wasn’t really dying.

It was just a little confused, that was all.

In recent years, I think that, after those new paradigms became well-established, they were employed and explored, and, to some extent, they were used up. Or at least, that is the way that a lot of musicians have taken it; the prevailing styles of the 2000s became seen as tired and trite near decade's end, including the wistful indie-rock sound (Death Cab for Cutie, Arcade Fire, Ra Ra Riot, Band of Horses) that blossomed over that time period. Rock no longer dominates the conversation the way it often did in the 1990s; R&B and hip-hop have now almost fully supplanted rock and non-dance-oriented pop as the predominant idioms, and both mainstream and fringe musicians question the value of spending so much time thinking about rock music as something worth “saving” - i.e. perpetuating. Like jazz and the blues, I believe more and more people are coming to the conclusion it may be time for rock to become a niche, a tradition defended and kept alive by devotees, rather than the default listening material for a generation.

But where will Rock lead? I don’t think anyone has a good answer to that question. We need to go somewhere, and we know it, but we haven’t heard a particularly compelling mission statement in quite a while, perhaps longer than a decade. That’s resulted in a raft of schizophrenic, kitchen-sink recent releases that stab wildly in new directions, trying (and, I think, often failing) to come up with a mix of old and new, far and near, that will result in artistically compelling new pathways. Examples abound: Animal Collective’s Merriweather Post Pavilion. Yeasayer’s Odd Blood. TV on the Radio’s Return to Cookie Mountain. Sufjan Stevens’s The Age of Adz. The Dirty Projectors. Vampire Weekend. M.I.A. and Sleigh Bells. Virtually everything Pitchfork has trumpeted in the past couple of years – post-dubstep, drag, chillwave, and most recently, awkward white kids rediscovering ‘90s R&B, like The XX, James Blake, and How to Dress Well. We have no idea what to do with music, so we’re trying everything. Again.

The results of this experimentation aren’t making much headway at radio, which is far less diverse than it used to be, and is arguably obsolete anyway. It’s being played out on blogs, on YouTube, on SoundCloud and BandCamp pages, and, of course, on albums, which are inevitably receiving limited-edition 180-gram splatter-marble double-LP treatments as statements of their preciousness. It’s indicative of the era that the new sounds (The Now Sounds?) are available in formats that are ultra-ephemeral and ultra-collectible all at once. An age of extremes, I guess.

Furthermore, some of this isn’t breaking out past the cool kids, and normal teenagers are still listening to stuff that does make radio and thus isn’t on the cool kids’ radar – the continuing mainstream still indebted to grunge (Nickelback, Breaking Benjamin, Sick Puppies, Shinedown); emo-pop and its related alternative tributaries (A Day to Remember, The Maine, The Ready Set, Never Shout Never); country (let’s never forget that this sells way more records than anyone who lives in a city ever gives it credit for); and, of course, pop, nowadays almost exclusively hip-hop and house-derived dance music.

But the weird stuff breaks through, still, every now and then. The albums by Animal Collective and Sufjan Stevens I mentioned above all cracked the Top 20 of the Billboard 200; Vampire Weekend went to #1; M.I.A. had a Top Ten hit single. Kanye’s new album – fucking strange. In a slightly different direction, I think Cage the Elephant, whose “Ain’t No Rest for the Wicked” sticks out noticeably among its peers at radio, harks back to those strange sounds that littered FM in the late nineties. That’s not to say that it’s better – in fact, I think a lot of the mainstream stuff the cool kids are missing is a hell of a lot better than what they obsess over – but it is, at least, making things interesting.

Comments